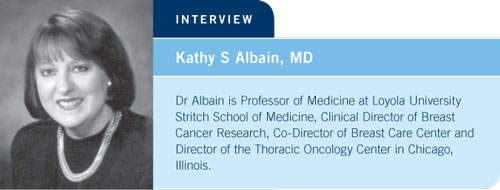

You are here: Home: LCU 1 | 2006 : Kathy S Albain, MD

| Tracks 1-13 |

| Track 1 |

Introduction by Neil Love, MD |

| Track 2 |

ECOG-E4599: Translating first-line

bevacizumab data into

clinical practice |

| Track 3 |

Selection of first-line therapy

for patients ineligible for

ECOG-E4599 |

| Track 4 |

Incorporating erlotinib into the

management of metastatic

NSCLC |

| Track 5 |

Identifying predictors of response

to EGFR TKIs |

| Track 6 |

Use of adjuvant chemotherapy in

patients with lower-risk disease |

| Track 7 |

Incorporating targeted therapies

into adjuvant clinical trials |

| Track 8 |

Continuation of bevacizumab

after disease progression |

|

| Track 9 |

RTOG-9309: Radiotherapy

concurrent with cisplatin/

etoposide with or without surgical

resection in Stage IIIA NSCLC |

| Track 10 |

RTOG-9309: Higher mortality

associated with pneumonectomy |

| Track 11 |

Docetaxel consolidation after

induction chemoradiation in

Stage IIIB disease |

| Track 12 |

Chemoradiation therapy for

patients with Stage III disease |

| Track 13 |

SWOG-S0229: Pulmonary

rehabilitation education with or

without exercise training |

|

|

Select Excerpts from the Interview

Track 2 Track 2

DR LOVE: Would you comment on ECOG-E4599, which evaluated

bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy in patients with

metastatic disease? DR LOVE: Would you comment on ECOG-E4599, which evaluated

bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy in patients with

metastatic disease? |

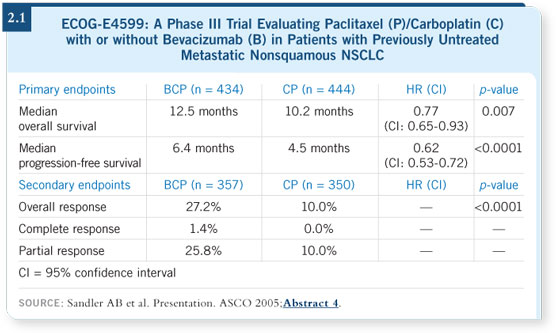

DR ALBAIN: The addition of bevacizumab makes carboplatin/paclitaxel a

better regimen. If you want to utilize carboplatin and paclitaxel in the front-line

setting and the patient meets the criteria for ECOG-E4599 (nonsquamous

histology and no history of uncontrolled hypertension, bleeding or clotting),

you should probably also administer bevacizumab (Sandler 2005; [2.1]). DR ALBAIN: The addition of bevacizumab makes carboplatin/paclitaxel a

better regimen. If you want to utilize carboplatin and paclitaxel in the front-line

setting and the patient meets the criteria for ECOG-E4599 (nonsquamous

histology and no history of uncontrolled hypertension, bleeding or clotting),

you should probably also administer bevacizumab (Sandler 2005; [2.1]).

DR LOVE: How do you approach the selection of chemotherapy in the first-line

setting for patients with metastatic NSCLC, and where does bevacizumab fit in? DR LOVE: How do you approach the selection of chemotherapy in the first-line

setting for patients with metastatic NSCLC, and where does bevacizumab fit in?

DR ALBAIN: Our goal is to enroll our patients on clinical trials. In the

Southwest Oncology Group, we’ve just finished a study (SWOG-S0342)

with cetuximab, either concurrent with or sequenced after carboplatin

and paclitaxel. DR ALBAIN: Our goal is to enroll our patients on clinical trials. In the

Southwest Oncology Group, we’ve just finished a study (SWOG-S0342)

with cetuximab, either concurrent with or sequenced after carboplatin

and paclitaxel.

As I mentioned previously, if you want to use carboplatin and paclitaxel as

your main regimen in this patient population, then you should add bevacizumab

(Sandler 2005).

There is a preclinical rationale for the combination of bevacizumab with a

taxane, and a lot of work is being done to evaluate other potentially additive

and/or synergistic combinations. So, hopefully, there’ll be more agents

to work with. I also use other regimens: cisplatin/docetaxel, cisplatin/

gemcitabine, and a number of others.

DR LOVE: How do you decide between those options on a case-by-case basis?

What are some of the factors you consider? DR LOVE: How do you decide between those options on a case-by-case basis?

What are some of the factors you consider?

DR ALBAIN: I consider the patient’s overall performance status and comorbid

illnesses. So if the patient, for example, has diabetes that’s quite difficult to

control, you may stay away from a regimen that requires steroids for a few

days. There are a lot of things that play into the decision-making in advanced

lung cancer. Patients often have a spectrum of other illnesses that go along

with prior smoking — poor lung function, et cetera. DR ALBAIN: I consider the patient’s overall performance status and comorbid

illnesses. So if the patient, for example, has diabetes that’s quite difficult to

control, you may stay away from a regimen that requires steroids for a few

days. There are a lot of things that play into the decision-making in advanced

lung cancer. Patients often have a spectrum of other illnesses that go along

with prior smoking — poor lung function, et cetera.

Track 7 Track 7

DR LOVE: Where do you see things heading with the next generation of

adjuvant trials in NSCLC? DR LOVE: Where do you see things heading with the next generation of

adjuvant trials in NSCLC? |

DR ALBAIN: We do need an adjuvant bevacizumab trial, and one is being

designed right now and will be conducted by the Intergroup. I believe that we also have to get erlotinib back in trials, because I can’t imagine that it

wouldn’t be helpful for minimal residual disease as opposed to very advanced

chemotherapy-refractory disease. DR ALBAIN: We do need an adjuvant bevacizumab trial, and one is being

designed right now and will be conducted by the Intergroup. I believe that we also have to get erlotinib back in trials, because I can’t imagine that it

wouldn’t be helpful for minimal residual disease as opposed to very advanced

chemotherapy-refractory disease.

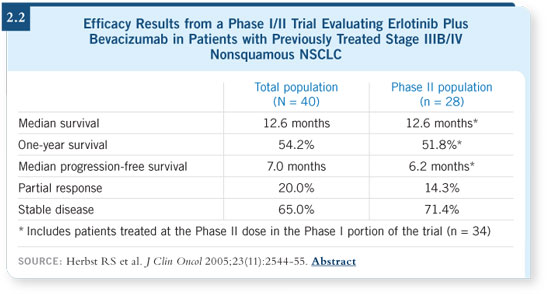

DR LOVE: What are your thoughts about the report by Herbst and Sandler

evaluating the combination of bevacizumab and erlotinib (Herbst 2005; [2.2])? DR LOVE: What are your thoughts about the report by Herbst and Sandler

evaluating the combination of bevacizumab and erlotinib (Herbst 2005; [2.2])?

DR ALBAIN: That’s a very interesting trial, and we’re participating in the

follow-up study. It’s an extremely provocative result, and it is worth testing the

combination of agents. Combining targeted agents is going to be important for

those tumors that aren’t driven by a dominant single pathway. DR ALBAIN: That’s a very interesting trial, and we’re participating in the

follow-up study. It’s an extremely provocative result, and it is worth testing the

combination of agents. Combining targeted agents is going to be important for

those tumors that aren’t driven by a dominant single pathway.

Tracks 9-10 Tracks 9-10

DR LOVE: Would you talk about the RTOG-9309 study? DR LOVE: Would you talk about the RTOG-9309 study? |

DR ALBAIN: RTOG-9309 evolved because of the large number of Phase II

trials conducted in the late 1980s and early 1990s that showed the feasibility of

sending patients for a resection following chemoradiotherapy. DR ALBAIN: RTOG-9309 evolved because of the large number of Phase II

trials conducted in the late 1980s and early 1990s that showed the feasibility of

sending patients for a resection following chemoradiotherapy.

Other trials were studying chemotherapy alone, but at least in the Southwest

Oncology Group’s series of pilot studies, we were evaluating a concurrent

chemoradiotherapy program that showed a lot of promise.

That was brought into two studies — the first a trimodality study with

surgery after the chemoradiation and the second with straight chemoradiation.

These trials not only showed feasibility, but they also raised some concerns

about a higher rate of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) after

surgery.

Additionally, these trials identified a group of patients who — even though

they had high-volume disease prior to therapy — at the time of surgery would

have no remaining disease in their mediastinal nodes. The pilot study observed patients with Stage IIIA (pN2) and IIIB (nonpleural effusion) disease. The big

debate, then, was whether surgery really contributes to survival.

Thus, SWOG started a Phase III trial while several other Phase III trials were

going on. The Intergroup decided to shut all of them down and start a new

one (RTOG-9309), which was identical to the SWOG design but was run by

the RTOG. RTOG-9309 limped along in its accrual for a number of years.

It was an extremely difficult study to discuss with patients because you had to

inform them of the possibility of a higher rate of postoperative death. The trial

finally recorded enough events for reporting, which were fewer than projected

because of the long duration of accrual.

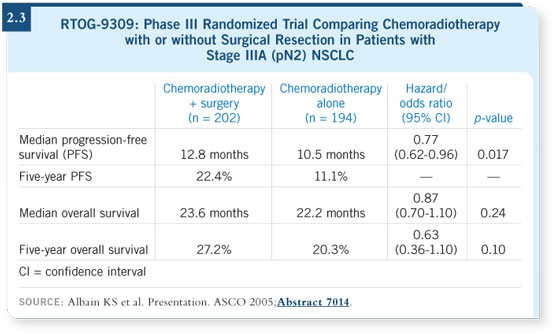

The first report showed a marked improvement in progression-free survival

with the addition of surgery. Reproducing what we had seen in the pilot

study, those patients with mediastinal nodes that were no longer positive after

chemoradiotherapy seemed to have the best outcome.

The overall survival, however, showed no difference; the tail of the curve was

a little bit separated, but the p-value was not significant (Albain 2003).

A final survival report was planned when more data were available, and we

presented it at ASCO 2005. We showed the same overall results in terms of

progression-free survival and overall survival (Albain 2005; [2.3]).

We looked very carefully at the postoperative deaths. We found — just as

we had in the pilot trial — that the majority of the postoperative deaths

occurred in patients who had undergone a pneumonectomy. These deaths

were predominantly from ARDS, just as other postoperative deaths we have

reported. The trial was not able to show an overall survival advantage because

of these postoperative deaths (Albain 2005).

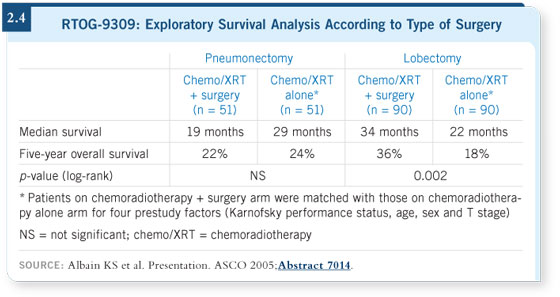

Our statistician performed an exploratory analysis matching the patients who

had undergone pneumonectomies to a similar group in the nonsurgical arm.

The same process was followed with the patients who had undergone lobectomies.

A dramatic split favored the lobectomy group over chemoradiotherapy

alone, whereas the patients who had pneumonectomies had a worse survival

rate than a matched group that did not receive surgery (Albain 2005; [2.4]).

That analysis was exploratory, but it answered the question, “What do I do

in practice?” These were the types of patients for whom the standard of care

would be chemotherapy and radiation. These were not the patients with very

minimal N2 disease, who could still undergo surgery.

If I see a patient with mediastinal disease who fits the criteria for the study, is

suited to undergoing a lobectomy, is fit and has a good performance status and

good pulmonary function, we discuss the study results.

Select publications

|